You became a superintendent for the first time during one of the most challenging times in our nation’s history. What are some things you were proud to have achieved during your very first year on the job?

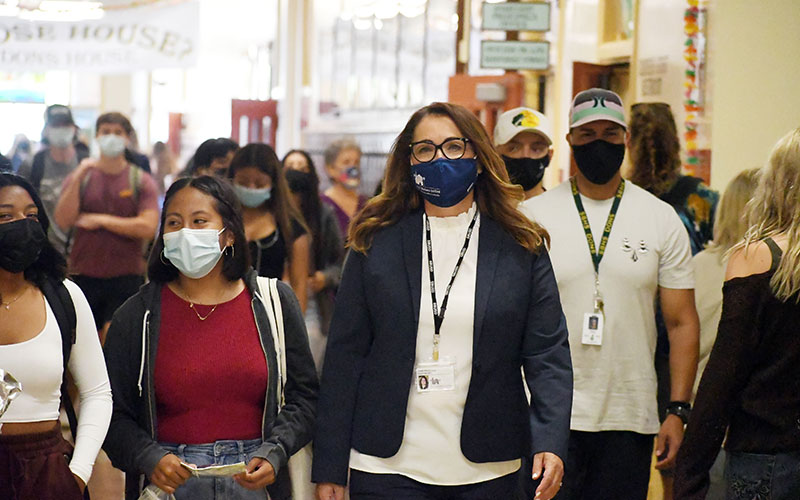

I’m very proud of keeping our students and staff safe during my first year as superintendent. It was important for me that I keep up with changes in health guidance and communicate them quickly to staff and families so we could work toward reopening schools in the safest way possible.

It was also important for me to focus on serving our Spanish-speaking families, as the majority of students enrolled in our district are Latina/o. I worked with public health officials and others on an equity agenda of information sharing on issues like testing and vaccines. This was also the case for some of our employees in food services and maintenance—they never took a day off from work and were truly heroes along with our teachers and administrators.

Working alongside our many stakeholders was key in helping to reopen schools. I collaborated closely with our labor partners early on, and also got to know the cabinet members and top leaders in the Santa Barbara community, while listening and learning from them and our staff and families.

How are the 2021-22 school year’s challenges different from last year’s? And how have you taken last year’s lessons into account when planning for this one?

This year’s challenges are very different. The rise in cases of children getting the Delta variant of Covid has caused more angst for all of us. We are now administering tests and doing active monitoring, contact tracing, quarantining when necessary, and administering vaccines for children and adults, whereas last year we focused only on vaccines and symptomatic testing for adults. The lessons from last year were how we organized ourselves to respond in teams so that we could maintain a focus on equitable outcomes for all students, along with clear and consistent communication.

The other strategy we used last year was keeping the Stockdale Paradox in mind—to remain optimistic while realistic. We remind ourselves of it often now as we deal with our current situation. In James Stockdale’s words: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose —with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

Overall, what we learned is that we can do equity work and great work if we collaborate, communicate, and put students at the center of all our decisions.

You’re one of a small number of people of Latina/o descent in a superintendent role in California, despite the high Latina/o population in the state. Do you see any signs of improvement in DEI in education since you began your career? What does the education community need to know or do to improve representation in leadership?

My doctoral dissertation at LMU was on the leadership practices that Latina/os bring to education. I conducted a national qualitative study of Latina/o leaders serving in education systems with significant populations of students who are Latino and English learners. My study found that Latinos bring a lens of a strong identity with a personal moral compass; many identify as bilingual/bicultural. We relate closely to families and students, especially if we serve in areas that we grew up in. And most importantly, we focus on community.

Many Latina/o teachers and staff are overlooked for promotions and find a lack of opportunities in leadership for them. That needs to change. Higher education and leaders of school systems must rethink how to recruit, retain, and promote their leaders. The skills needed in today’s global world, and as we continue to deal with a global pandemic, the multilingual and collaboration skills are musts.

While I’ve seen some improvements in DEI since I began working in education, I don’t feel it’s moving fast enough. We continue to get stuck at the “talking about it” stage. I’m more interested in action-based equity work: Will we really hire more leaders of color? Will we look at English-only tests and ask ourselves if they are a true measure of a student’s knowledge if they are not yet fluent in that language? Do we have the courage to change our systems, so that the underrepresented and marginalized are lifted?

You worked in education for a long time prior to earning your Ed.D. Why did you decide to pursue a doctoral degree?

I pursued an Ed.D. because I wanted to reach the next level of school leadership, and I thought having a doctorate would add to my resume for this purpose. But I got so much more from the experience than I expected. I chose LMU because of its tradition and history of commitment to equity and social justice. After so many years in education, I’ve seen too many commitments made about these matters without actionable strategies behind them. In education, we’ve been reacting to policies that are not driven by social justice or equity, but by politics.